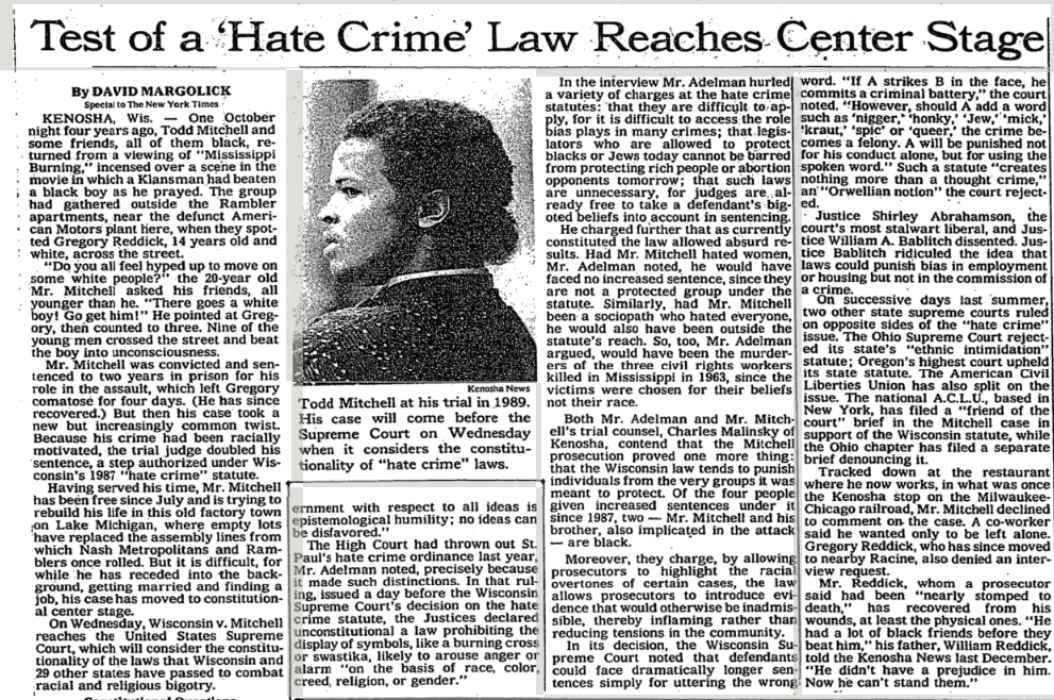

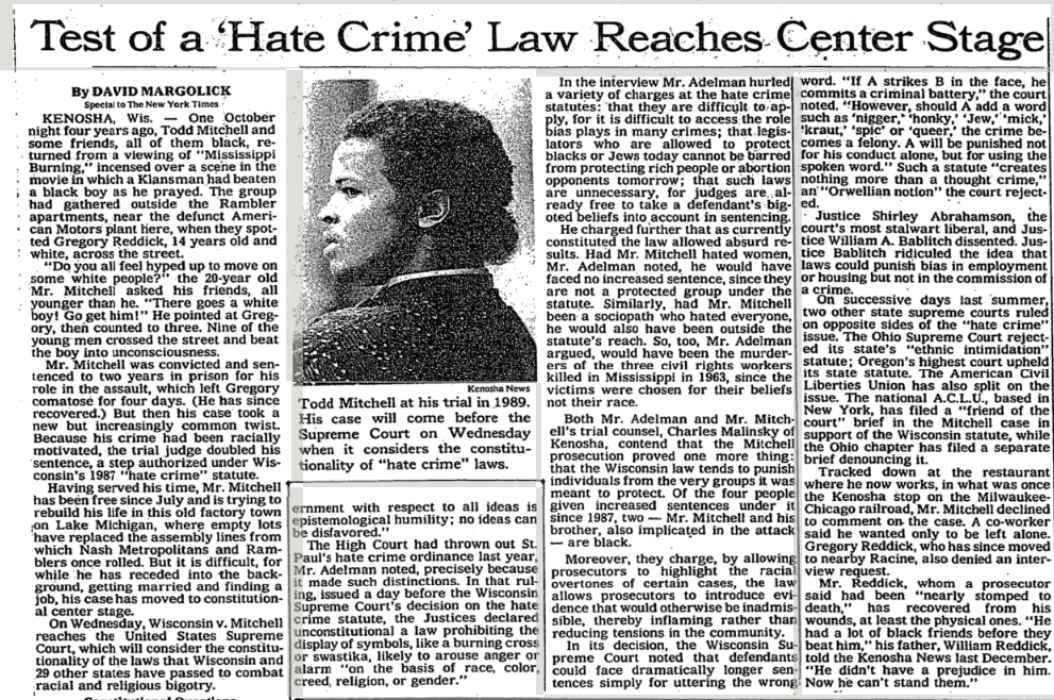

The Supreme Court in 1993 upheld a Wisconsin hate crime statute that allowed longer prison times if a criminal chose their victim on the basis of "the victim's race, religion, color, disability, sexual orientation, national origin or ancestry." The case Wisconsin v. Mitchell stemmed from an assault by a group of young black men on a 14-year-old white boy. Todd Mitchell, prior to the attack, had said "Do you all feel hyped up to move on some white people?" He claimed the hate statute that allowed enhanced penalties was a violation of the First Amendment in restricting speech. The court disagreed, saying the statute punished conduct, not speech. (Image of New York Times article about the case, April 20, 1993)

In Wisconsin v. Mitchell, 508 U.S. 476 (1993), the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that there is a meaningful distinction between punishing the content of speech and using speech as evidence of motive in a crime.

This case followed closely on the heels of R.A.V. v. St. Paul (1992), in which the Court ruled that restricting speech specifically because it targeted people based on race was unconstitutionally underinclusive under the First Amendment. Mitchell would address some of the concerns highlighted in R.A.V.

In 1989, a group of young black men who had just watched the movie Mississippi Burning decided to attack a young white man. They beat the man, rendering him unconscious and leaving him in a coma for four days.

Prior to the attack, Todd Mitchell, one the attackers, said, “Do you all feel hyped up to move on some white people? . . . There goes a white boy; go get him.” Mitchell was found guilty of aggravated assault, a charge that carried a maximum prison sentence of two years. However, the jury also found that Mitchell had chosen his victim specifically because of the victim’s race, and so Mitchell was sentenced instead to four years in prison under a Wisconsin penalty enhancement statute.

The statute, known as a “hate crimes” statute, provided a longer maximum sentence for crimes where the accused has selected victims on the basis of “the victim’s race, religion, color, disability, sexual orientation, national origin or ancestry.” Mitchell contended that the penalty-enhancement statute violated his First Amendment rights.

The Wisconsin State Supreme Court, reversing the appellate court decision, ruled in favor of Mitchell. However, the U.S. Supreme Court reversed the state court ruling, finding that the statute covered action, not speech, and that it was not overbroad.

Chief Justice William H. Rehnquist, quoting Dawson v. Delaware (1992), explained, “The Constitution does not erect a per se barrier to admission of evidence concerning one’s beliefs and associations at sentencing simply because those beliefs and associations are protected by the First Amendment.” He offered as an example sexual harassment law, as well as laws that make it illegal for an employer to discriminate on the basis of race, color, religion, or national origin.

Rehnquist directly addressed R.A.V., which found the Bias Motivated Crime Ordinance to be unconstitutional under the First Amendment.

The ordinance had made it illegal to use language or symbols targeting people on the basis of “race, color, or creed.” The majority in R.A.V. found the ordinance unconstitutional because it was content-based.

Rehnquist distinguished Mitchell from R.A.V.: “But whereas the ordinance struck down in R.A.V. was explicitly directed at expression, the statute in this case is aimed at conduct unprotected by the First Amendment.” In regard to Mitchell’s overbreadth claim, the majority found that it would take “too speculative a hypothesis” to imagine a situation where the statute would cause a chilling effect on speech.

This article was originally published in 2009. Chris Demaske is an associate professor of communication at the University of Washington Tacoma. Her research explores issues of power associated with free speech and free press and has covered topics including hate speech, academic freedom, and Internet pornography.