One unintended feature of the United States’ income tax system is that the combined tax liability of a married couple may be higher or lower than their combined tax burden if they had remained single. This is called the marriage penalty or marriage bonus.

Marriage penalties and bonuses have a significant impact on the combined tax burden of couples. Marriage penalties affect taxpayers at very high and very low incomes, and marriage bonuses affect many middle-income couples with disparate incomes. Taxpayers with children also face large penalties and bonuses for marriage. While it is possible to eliminate the marriage penalty and bonus, which would make the tax code more neutral with respect to marriage, it would take a significant change to the United States’ income tax code. As a result, lawmakers may opt for smaller marriage penalty reliefs as they have in the past.

A marriage penalty or bonus is the change in a couple’s total tax bill as a result of getting married and thus filing their taxes jointly. The degree to which the marriage penalty or bonus affects any given couple depends on the level of their combined income, the extent to which their individual incomes are similar, and the number of children they have.

The marriage bonus typically occurs when two individuals with disparate incomes marry. When an individual with a higher income marries and files jointly with an individual with a much smaller income, the additional income is usually not enough to push the couple’s combined income into a higher tax bracket. However, due to the much wider income tax brackets A tax bracket is the range of incomes taxed at given rates, which typically differ depending on filing status. In a progressive individual or corporate income tax system, rates rise as income increases. There are seven federal individual income tax brackets; the federal corporate income tax system is flat. for married individuals, much of the couple’s income falls into lower tax brackets. The result is a lower tax bill.

Suppose an unmarried couple earned a total of $60,000, but the distribution was unequal: $20,000 from the first partner and $40,000 from the second (Table 1). As an unmarried couple, their combined tax bill is $8,560. When the couple gets married and combines their incomes, their taxable income Taxable income is the amount of income subject to tax, after deductions and exemptions. For both individuals and corporations, taxable income differs from—and is less than—gross income. remains the same. However, the tax brackets for married couples widen. This means that less of the couple’s income is taxed at the 12 percent marginal tax rate than it was when they were not married. As a result, their combined tax bill would fall by $31 to $8,529.

Tax Bill of Married and Unmarried Couple with No Children

Income

Income Tax

Total Tax

Marriage penalties typically occur when two individuals with similar incomes marry. Prior to the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA), the marriage penalty was especially pronounced for medium- to high-income earners because the income tax brackets for married couples at the top of the income tax schedule were not twice as wide as the equivalent brackets for single individuals. Currently, however, all tax brackets for married filers are exactly double those for single filers, except for the top 37 percent marginal rate. As such, marriage penalties are generally only felt at very high income levels.

An unmarried couple with equal incomes that earn a combined $1,000,000 would have a total tax bill of $328,837.80 ($292,979.00 from the individual income tax, $30,458.80 from the payroll tax A payroll tax is a tax paid on the wages and salaries of employees to finance social insurance programs like Social Security, Medicare, and unemployment insurance. Payroll taxes are social insurance taxes that comprise 24.8 percent of combined federal, state, and local government revenue, the second largest source of that combined tax revenue. , and an additional $5,400.00 from the Medicare surtax). If they were to get married, they would be hit by a relatively small marriage penalty of $890.60 (Table 2). This penalty comes from two different taxes.

First, the narrower top tax brackets for married individuals push more of their taxable income into the 37 percent marginal tax bracket. In addition, their combined income as a married couple would push their income to be more greatly affected by the Medicare Surtax A surtax is an additional tax levied on top of an already existing business or individual tax and can have a flat or progressive rate structure. Surtaxes are typically enacted to fund a specific program or initiative, whereas revenue from broader-based taxes, like the individual income tax, typically cover a multitude of programs and services. of 0.9 percent on income over $250,000. When unmarried, both only had to pay the Medicare surtax on less than half their income because the surtax only applies to income over $200,000 for singles.

Tax Bill of Married and Unmarried Couple with No Children

Income

Taxable Income

Income Tax

Payroll Tax

Medicare Surtax

Total Tax

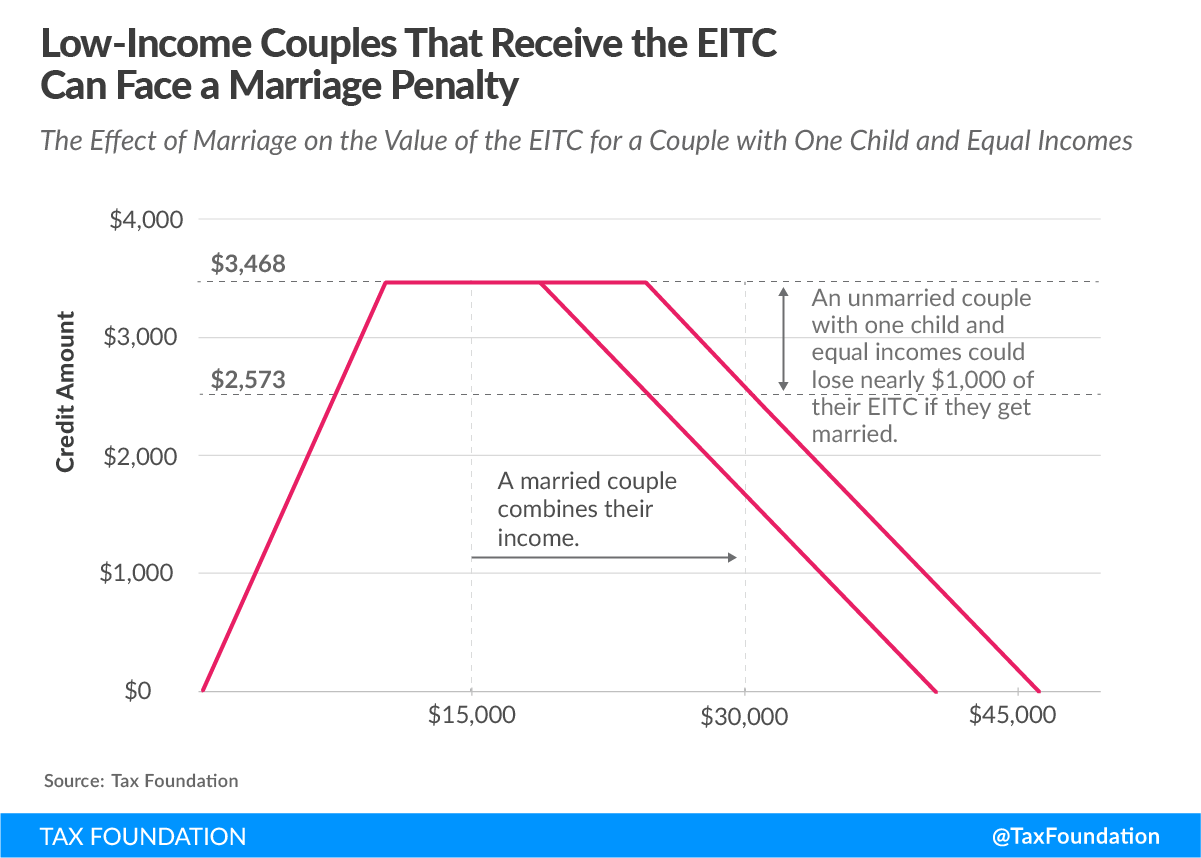

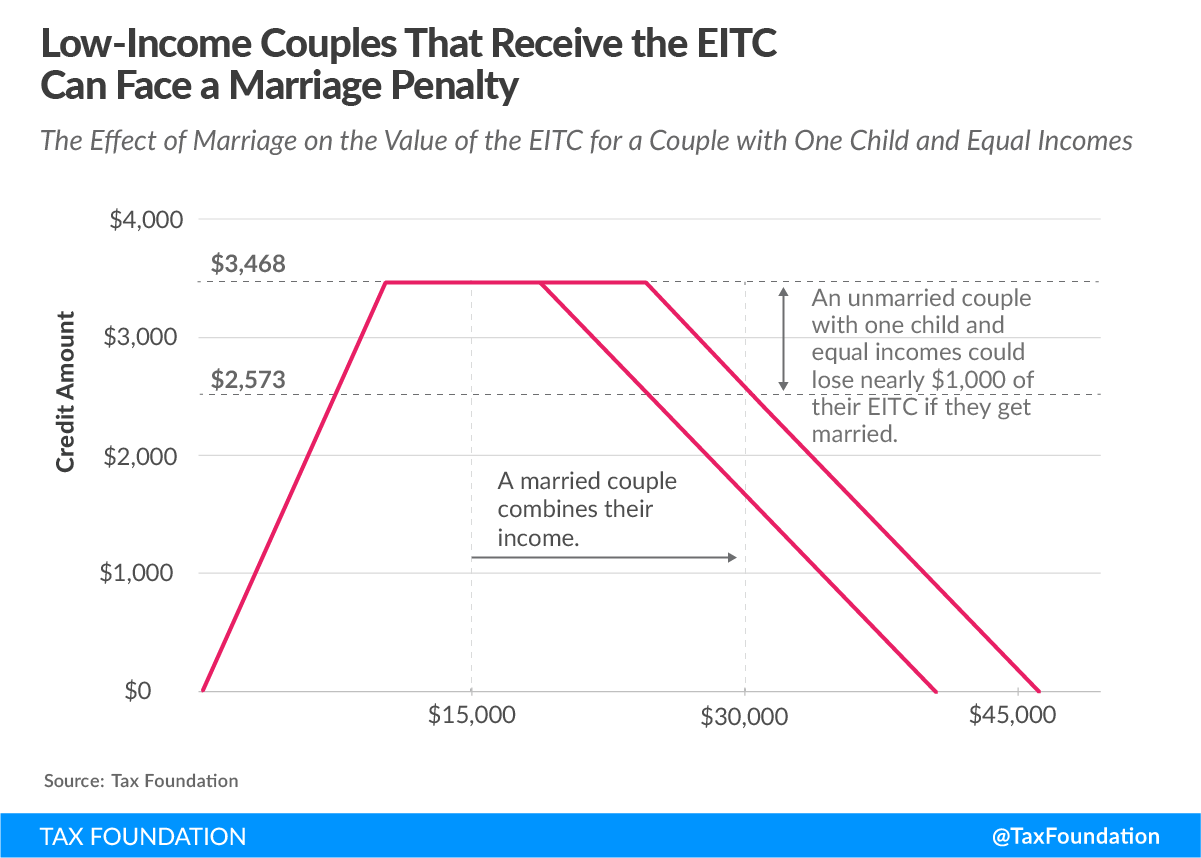

For low-income individuals, the Earned Income Tax Credit A tax credit is a provision that reduces a taxpayer’s final tax bill, dollar-for-dollar. A tax credit differs from deductions and exemptions, which reduce taxable income, rather than the taxpayer’s tax bill directly. (EITC) has a significant impact on marriage penalties and bonuses. Adding one partner’s income to the other partner’s income can easily push the combined income of the couple into the phaseout range, or further into the phase-in of the EITC, resulting in a reduction or increase of the couple’s combined after-tax income.

Table 3 shows an example of a couple with equal incomes of $15,000 ($30,000 combined) with one child. Unmarried, their total tax bill would be -$2,296.71 due to the partial refundability of the $2,000 Child Tax Credit (CTC) and the $3,468 EITC received by the individual who claimed the child. If they were to marry, their combined tax bill would still be negative, but they would face a marriage penalty of $618.60.

Tax Bill of Married and Unmarried Couple with One Child

Income

Taxable Income

Income Tax

EITC

CTC

Refundable CTC

Payroll Tax

Total Tax

There are two reasons why this couple is hit with a penalty. First, when the couple is unmarried, one individual can claim head of household, which provides a larger standard deduction and wider tax brackets. When married, the couple loses the benefit of head of household status, which results in higher combined taxable income.

Second, as an unmarried couple, one of the parents could claim their child for the EITC and receive the full amount of $3,468.00 with the income of $15,000 (Figure 1). However, when married, their total income of $30,000 pushes them into the phaseout range of the EITC, reducing the credit amount by about $1,000.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

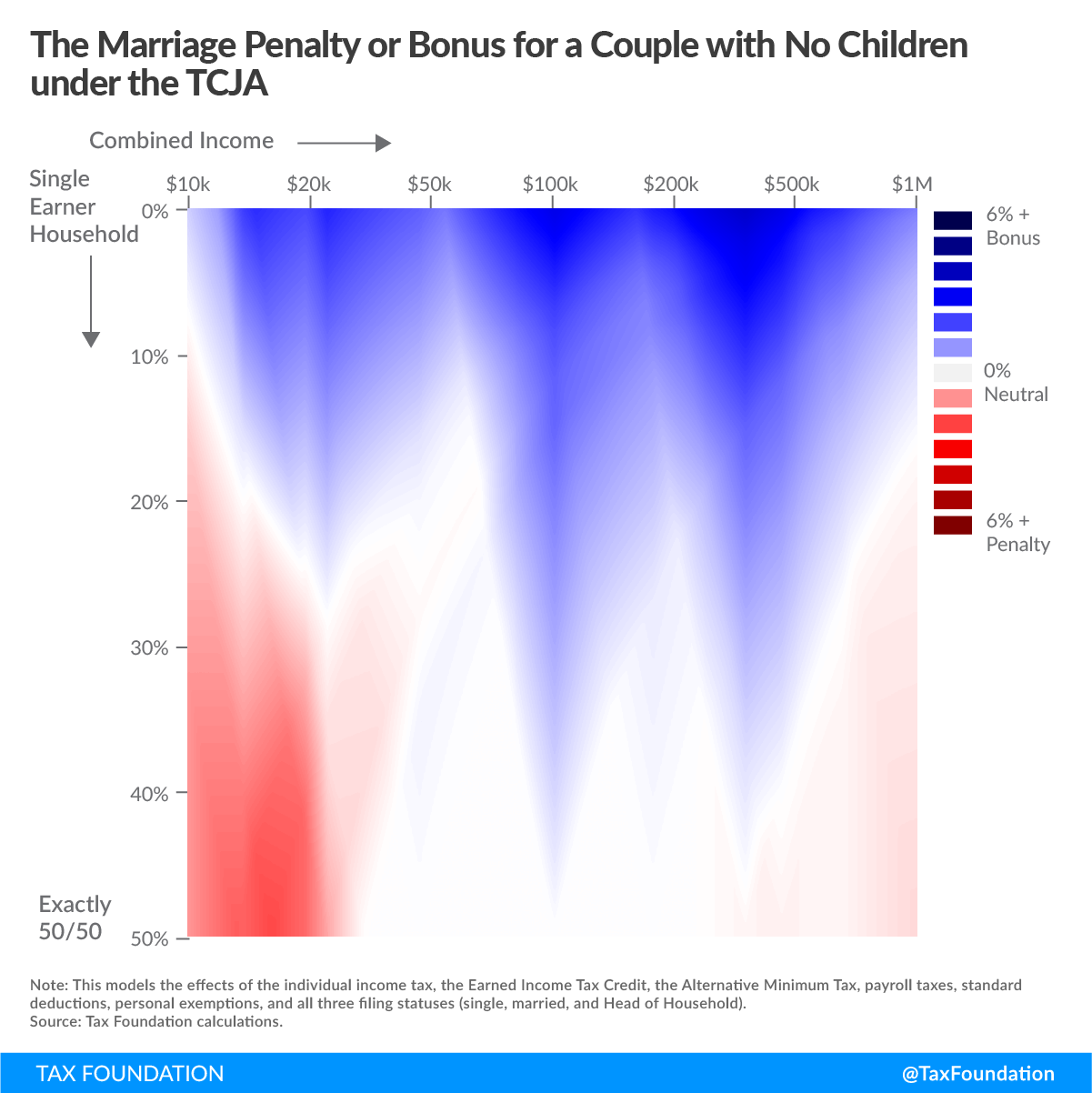

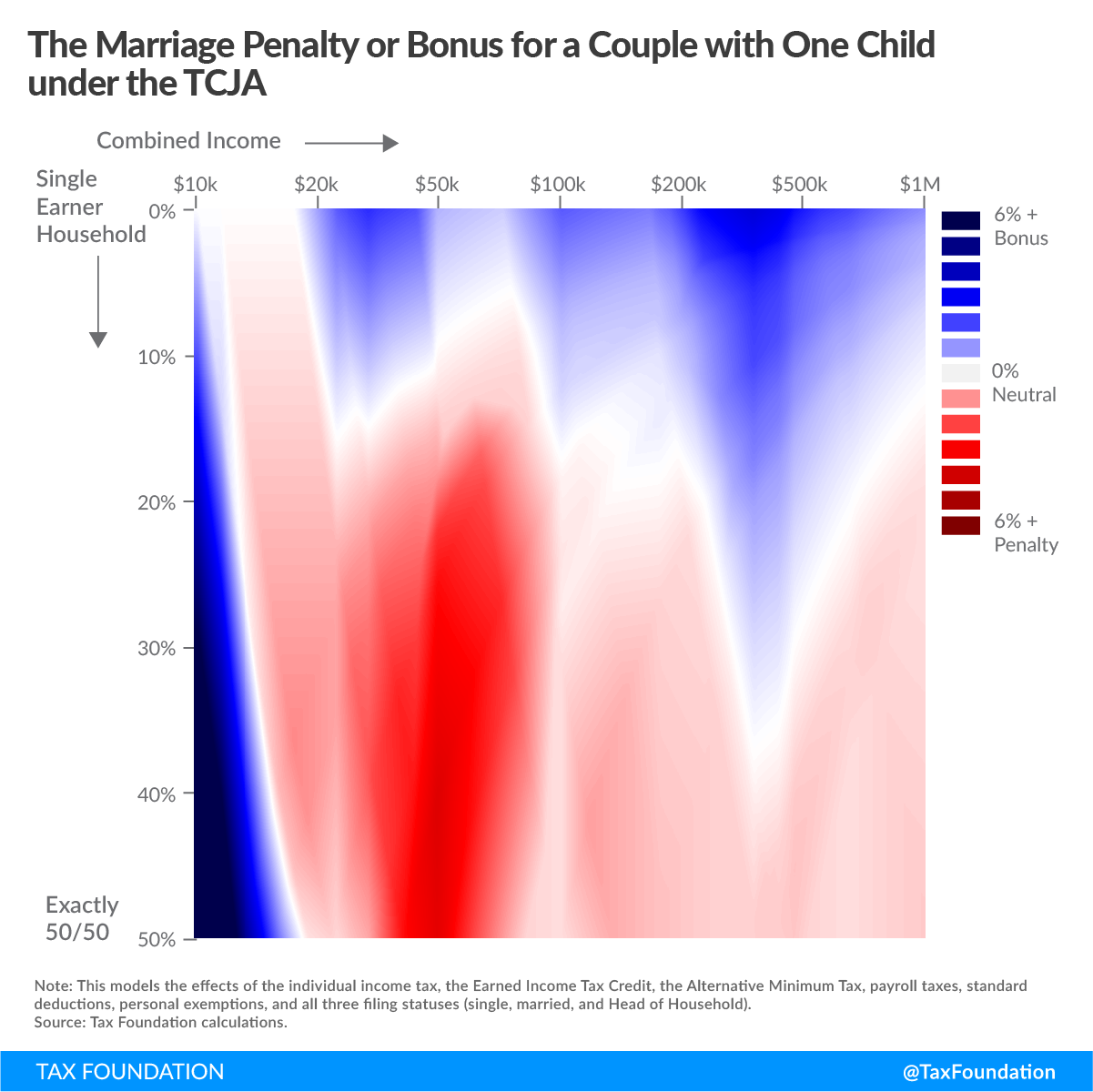

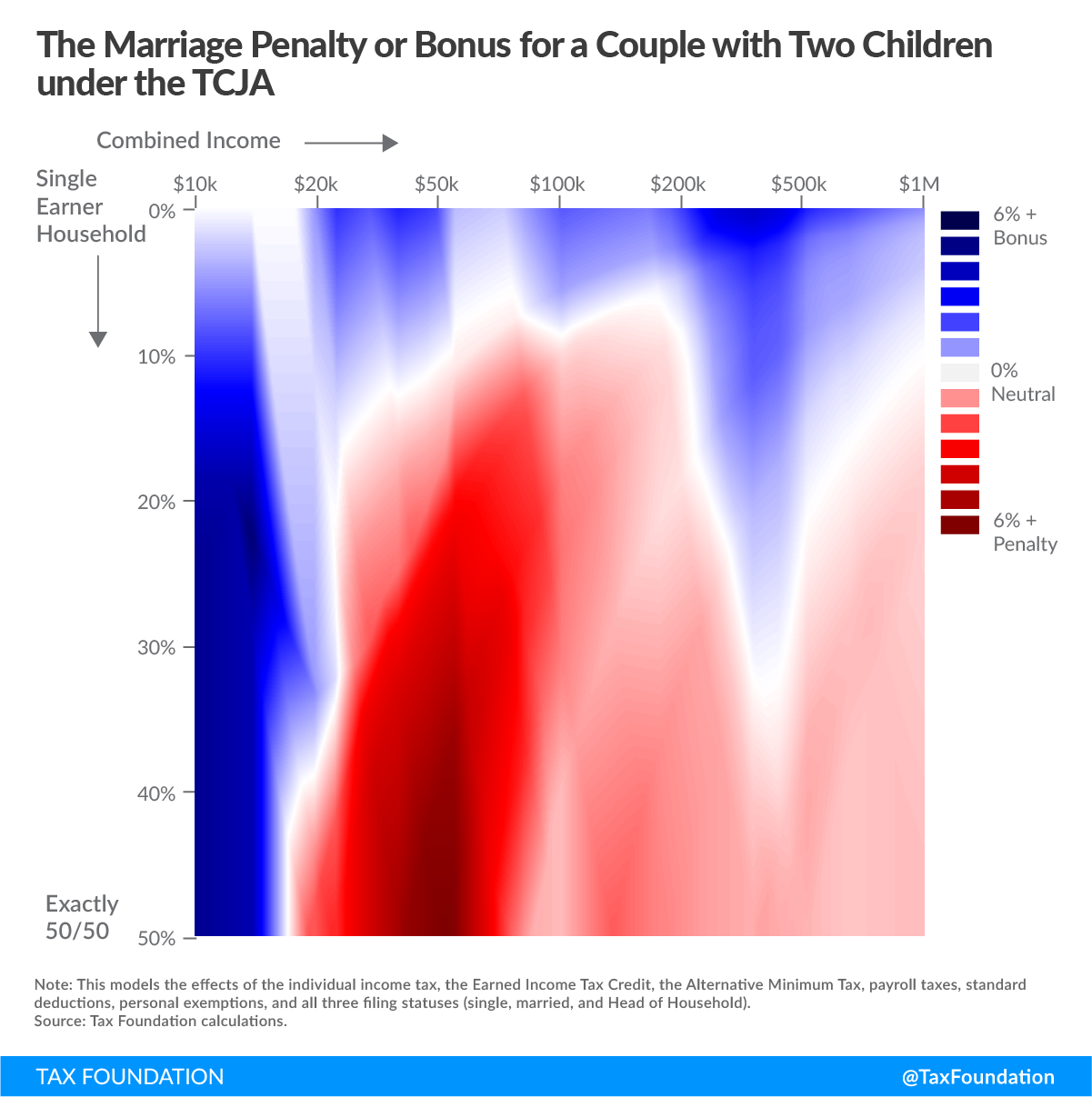

There are several areas in the tax code in which the marriage penalty and marriage bonus affect taxpayers. In the following figures, we modeled the effects of marriage on a couple’s tax bill given two factors: the level of income and the equality of the couple’s income (from a couple with one earner to a couple with equal incomes). This is done for a household with no children, one child, and two children.

Each figure’s X-axis is a measure of income from $10,000 to $1 million and Y-axis is the equality of a couple’s income from a single earner to a 50-50 split, with the percent representing the share of the couple’s income by the second earner.

Areas in the figure shaded blue represent marriage bonuses and areas shaded red represent marriage penalties. The depth of the color represents the size of the marriage penalty or bonus as a percent of a couple’s total income.

The first figure shows marriage penalties and bonuses for couples without children. It shows that marriage penalties exist for low- and high-income couples with more equal incomes. As discussed, low-income marriage penalties are due to the phaseout of the EITC. High-income penalties are due to narrower tax brackets for greater combined incomes. Marriage bonuses occur mainly for taxpayers with disparate incomes. The income tax is relatively neutral for couples with combined incomes between $40,000 and $150,000 that are relatively equally distributed.

With no children, marriage bonuses can be up to 8 percent of a couple’s income, and penalties can be as large as 4 percent.

The next figure shows that the individual income tax An individual income tax (or personal income tax) is levied on the wages, salaries, investments, or other forms of income an individual or household earns. The U.S. imposes a progressive income tax where rates increase with income. The Federal Income Tax was established in 1913 with the ratification of the 16th Amendment. Though barely 100 years old, individual income taxes are the largest source of tax revenue in the U.S. becomes much less neutral with respect to marriage when a couple has a child. The EITC, which is a major driver of marriage penalties for low-income individuals, phases out much faster when the taxpayer has a child.

Marriage bonuses also become more pronounced for low-income couples with one child. Both the CTC and the EITC have steep phase-in benefits with one child. This means a low-income, unmarried couple could decrease their total tax bill through marriage, which would add their incomes together and increase the size of their EITC and CTC.

With one child, marriage bonuses can be up to 21 percent of a couple’s income, and penalties can be as large as 8 percent.

The distribution of marriage penalties and bonuses for couples with two children looks similar to the distribution for couples with one child, but the severity of penalties and bonuses is greater. With two children, the number of possible bonuses slightly increases for low-income couples but significantly declines for higher-income couples.

With two children, marriage bonuses can be up to 13 percent of a couple’s income, and penalties can be as large as 12 percent.

Marriage penalties and bonuses in the income tax code violate neutrality. An unmarried couple and a married couple with identical combined incomes may be treated differently. In addition, the penalties and bonuses could impact people’s behaviors in two ways.

A change in a couple’s total tax bill through marriage could conceivably alter that couple’s decision to get married. For example, a couple that is facing a $5,000 tax increase for simply getting married may second-guess their commitment. Conversely, a marriage bonus may induce a couple that is otherwise on the fence about marriage to tie the knot. However, most economic research has found that marriage penalties and bonuses have little to no effect on whether a couple will marry.

Secondly, marriage penalties or bonuses may affect how much each spouse works. When couples get married and combine their incomes, one or both partners could face higher or lower marginal tax rates on their next dollar of income, which could affect their incentives to work.

For example, if an unmarried couple with $40,000 of income earned by one partner gets married, the couple as a whole gets a marriage bonus of about $1,569.50. However, this bonus has different impacts on the marginal tax rates on each partner’s next dollar of income. The spouse who earns the $40,000 as a single used to face a 19.65 percent marginal tax rate The marginal tax rate is the amount of additional tax paid for every additional dollar earned as income. The average tax rate is the total tax paid divided by total income earned. A 10 percent marginal tax rate means that 10 cents of every next dollar earned would be taken as tax. on income. Once married, the marginal rate would decrease to 17.65 percent. However, the second earner, who unmarried would have faced a 0 percent marginal tax rate as a single, now faces the 17.65 percent marginal tax rate on the first dollar of income earned.

| Spouse 1 | Spouse 2 | |

|---|---|---|

| Unmarried Couple | ||

| Income | $40,000 | $0 |

| Marginal Rate on next dollar of income | 19.65% | 0% |

| Married Couple | ||

| Marginal Rate on next dollar of income | 17.65% | 17.65% |

| Change in Marginal Rate | -3.00% | 17.65% |

According to the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), these changes in marginal rates matter. The tax effect of marriage motivated higher-earning spouses (such as the spouse who earned the $40,000) to work between 0.1 and 0.3 percent more than they would if they had remained single, due to the lower marginal tax rates on average. Meanwhile, second earners in the household worked 7 percent less, due to the higher marginal tax rates they now face. Overall, the CBO found that the earnings of couples who file jointly are between 0.7 and 1.2 percent lower than they otherwise would have been if they remained single. [2]

The reason there are marriage penalties and bonuses is that the U.S. tax code simultaneously attempts to satisfy three conflicting goals: equal treatment of married couples, equal treatment of married and unmarried couples, and progressive taxation. [3]

To completely eliminate marriage penalties or bonuses in the tax code, it would require giving up one of these goals. For example, if the United States created a perfectly flat individual income tax with no provisions such as the Child Tax Credit or Earned Income Tax Credit, marriage penalties and bonuses would be eliminated. Likewise, if the United States kept its current progressive individual income tax but eliminated the ability for married couples to file jointly, there would also no longer be a penalty or bonus for marriage.

Changes that would eliminate marriage penalties and bonuses would drastically impact the current distribution of taxes paid and would be politically difficult to accomplish. As a result, Congress has opted to incrementally reduce the effects of the marriage penalty rather than regulate complete neutrality. In 2001, Congress passed a bill that widened the 15 percent tax bracket for married individuals. Next, Congress temporarily limited the marriage penalty in regard to the EITC. This temporary 2009 reform increased the level of income at which the EITC phased out for married couples and was made permanent in 2015. [5] Most recently, with the passage of the TCJA, all married brackets but the top marginal 37 percent bracket were set to be exactly double those of the single brackets, leading to less of an overall marriage penalty for middle- to high-income earners.

Marriage penalties and bonuses are a way that the income tax code violates the principle of neutrality. These penalties and bonuses potentially affect people’s behavior, especially whether to work. It is possible to completely eliminate both marriage penalties and bonuses, but it would require a significant overhaul of the tax code that drastically changes the current distribution of income taxes paid. Short of a complete overhaul, it is possible to reduce marriage penalties in the tax code, such as a permanent extension of marriage penalty relief for the Earned Income Tax Credit and widening the income tax brackets for high-income taxpayers filing jointly.

Subscribe to get insights from our trusted experts delivered straight to your inbox.

To measure marriage penalties and bonuses for incomes between $10,000 and $1 million, a few simplifying assumptions were made:

The following provisions were modeled: