by Teachwire

What's included?KS1, KS2, KS3, KS4

Are you struggling to juggle what seems like an endless number of reading abilities that require different level texts? Why not try reciprocal reading?

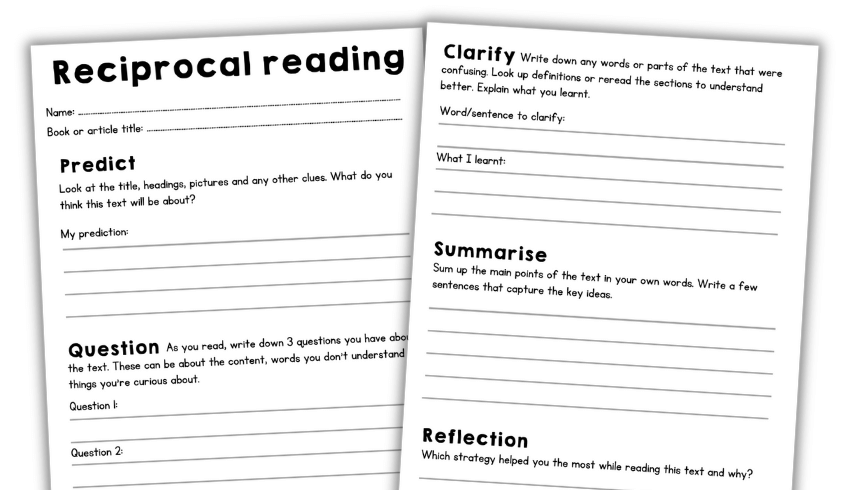

This free worksheet helps guide students through the reciprocal reading process, encouraging active engagement and improvement of comprehension skills.

Find out all about reciprocal reading and how to use it in your classroom below.

Also referred to as reciprocal teaching, reciprocal reading is a technique which does not use differentiation through text difficulty during reading lessons (Cooper and Grieve, 2009).

At its heart, it is a technique that develops reading comprehension by centring on the use of four key strategies:

Students take turns (with explicit modelling by you, the teacher) at being ‘predictor’, ‘clarifier’, ‘questioner’ and ‘summariser’.

In reciprocal reading you use the same text for all learners. Differentiation occurs through question styles relating to Bloom’s Taxonomy. How happy would our university lecturers be knowing that good old Bloom’s is being used?

Taking the time to explore misconceptions is a key feature of reciprocal reading. It stops children from ‘glossing over’ words they don’t recognise.

A meta-cognitive reciprocal reading approach helps all readers to fully understand the thinking processes involved in generating and answering in-depth questions accurately. In turn, this can improve reading comprehension performance across a range of diverse learners.

Here are top tips to begin your reciprocal reading journey.

Don’t just choose an age-appropriate text you think the children will enjoy. Choose a text that interests you or that you genuinely enjoy.

This may seem pretty obvious, but I sometimes feel it’s definitely overlooked. If you’re not excited to teach with it, how can you expect the children to be excited to engage with it?

Make reading part of your everyday classroom routine. The more children read and are exposed to a range of different texts, as well as vocabulary, the more they will learn.

You can achieve this through simple tasks such as displaying a ‘Word of the Day’ and providing an example of the word used in context, or by simply reading a book with the class.

I have found reading a class text, even if it is just an online news article, is a great tool in helping me to assess reading comprehension of unknown texts.

During reading sessions, use discussions by providing language stems to prompt readers to develop their own knowledge. For example:

| Skill | Language stems |

| Prediction: Use clues to make logical predictions | I think that… I think we will find out more about… I think (name) is feeling… because… |

| Clarify: Identify parts that are confusing and formulate understanding | What does the word … mean? Can you explain what … ? Why does (name) … ? |

| Question: Ask questions based on the text | Why does it say … ? How/why did … ? How is … an example of … ? How do (name) and (name) compare? |

| Summarise: Reiterate the main ideas in their own words | The text is about… The main ideas are… The author’s key points are… The important concepts are… |

Try to incorporate any of the four key strategies into your everyday teaching, regardless of the lesson or subject.

Reading skills can be developed in any areas of the curriculum. The prediction strategy can work particularly well in science. Ask learners to use what they already know to make a prediction.

I have also found history is a great subject to learners’ questioning skills. You can begin lessons by giving a stimulus (in the form or a primary or secondary source). Ask the class, ‘What questions could we ask to help us learn more about this time period?’

This would also be a perfect opportunity to highlight what clues you’re using to formulate the questions, using inference skills.

I’ve found pupils have really enjoyed ‘Prediction Puzzle’. This is where the class have to see if they can identify what we will be reading.

I give the children three clues and they are allowed three questions to guess the topic of our next text.

It has been a great tool in not only creating a real ‘buzz’ about reading, but also improving questioning and inference skills.

It can also be used in any subject. As an English lecturer once told me, the more links you can make to reading, the easier the teaching of reading will be.

Remember, throughout lessons try to explicitly model useful reading behaviours whenever possible:

You are the most important and crucial teaching aid in that classroom, and you do know what you are doing (even though it sometimes doesn’t feel like it).

Mia Brough is a Year 5 teacher in a junior school in the West Midlands. Follow her on Twitter at @MissB_Primary.

Yes, guided reading and reciprocal reading are different approaches to reading instruction.

Guided reading involves working with a small group of students who are at a similar reading level. You provide structured support and scaffolding to help students develop specific reading strategies and skills, often focusing on decoding and fluency.

Reciprocal reading is a more interactive and collaborative approach where students work in small groups and take turns leading the discussion. The teacher acts as a facilitator rather than the primary instructor.

In essence, guided reading is more teacher-directed, while reciprocal reading encourages student-led discussions and active participation.

Yes, you can adapt reciprocal reading so you can do it as a whole class activity. Start by explaining and modelling the four key strategies (predicting, questioning, clarifying, summarising).

Assign different roles to various students, then read a text aloud to the class. Pause at appropriate points to allow the designated students to perform their roles.

Next, facilitate a class discussion where each student in the role shares their insights. Encourage other pupils to contribute and discuss the points raised.

Regularly rotate the roles so that all students get the opportunity to practise each of the four strategies.

Yes, you can adapt reciprocal reading for individual use. Here’s how pupils can do it.

Before they start reading, ask pupils to look at the title, headings, and any images or captions. Can they make predictions about what the text will be about and what they might learn?

As they read, pupils should ask themselves questions about the content. These can be questions about the main ideas, details or vocabulary.

When they come across something confusing or unfamiliar, pupils should pause to clarify. They can look up definitions of unknown words, reread difficult sections or use context clues to enhance their understanding.

After reading a section, pupils can summarise the main points in their own words. This helps to reinforce comprehension and retain information.

Use our reciprocal reading worksheet, available at the top of this page, to assist.

Yes, you can begin to practise reciprocal reading with very young children by doing the following:

As they gradually master reciprocal reading, children will be able to read for meaning with greater ease and monitor their understanding before, during and after reading.

Head of English, Amanda Ellison, looks at the research behind reciprocal reading and explains how she’s utilised it in her own school…

In our school we identified 16 children whose reading ages were below their chronological ages. We tested them using the New Group Reading Test, which was to be our starting point.

From this initial group, we then selected two groups of four for targeted reciprocal reading sessions over a six-month period, with the remaining eight acting as a control group.

Before commencing, we issued the two focus groups with a questionnaire about their reading. Feedback confirmed what we already suspected – that struggling readers don’t like reading.

Their responses included comments like, ‘It’s boring’ and ‘I struggle to concentrate’. Only one said anything even slightly positive: ‘It passes the time.’

As the sessions got underway, problems soon materialised. Our designated timeslot was morning registration, hence children would habitually be absent or late. This was a sharp reminder for us to consider logistics next time, which highlighted the need for whole-school commitment.

Some children also felt singled out, and were borderline hostile. This wasn’t a great starting point.

Over time, though, our four-pronged strategy did show some signs of promise. The focus groups improved their reading ages by an average of 1.2 years, while the control group’s average advancement amounted to 0.8 years.

Moreover, some of the children reported feeling more confident about reading.

Had we found a solution to the post-lockdown reading deficit? A project such as ours is probably too small-scale to warrant a definitive thumbs-up at this stage.

However, the indicators suggest that it could certainly form part of the solution – particularly when used alongside other strategies, such as re-reading.

In any case, the process certainly produced some valuable findings. It highlighted the potential that reciprocal reading has as a literacy strategy. It also highlighted the need for systemic approaches when raising standards in that most precious skill of reading. And so, we keep on trying.

Research into reciprocal reading by the Education Endowment Foundation yielded interesting findings. Utilising reciprocal reading on a universal basis level improves metacognition rather than improving reading age (still valuable in itself, I’d say).

However, using the same strategy with focus groups – particularly FSM children – points to tangible improvements.

Amanda Ellison (@AellisonWrites) is head of English at an 11 to 16 school in South Tyneside, as well as a freelance writer and prolific book reviewer; for more information, visit ellisonwrites.co.uk